AJ Tapia-Wylie

Drug Cartels Do Not Exist: Narcotrafficking in US and Mexican Culture by Oswaldo Zavala, trans. William Savinar, Vanderbilt University Press, 2022, 206 pages, $34.95

Growing up in San Antonio, Texas, my family and I maintained a closeness to northern Mexico. I had family along the border states, and though I knew that they existed, I had never really spoken to them. When I expressed my desire to go across the border, my family warned me of the dangers that awaited me in Mexico. One particularly frightening text message, the topic of much family discussion, showed someone’s decapitated head, stuffed into a soccer ball and sent to the victim’s family by drug traffickers. Media attributed the act to the criminal monolith the narco. The cartels, I was told, were the ultimate source of disruption and carnage along the border; their power was so immense that their power reached over the border. Even El Paso was a dangerous place.

I was astounded when I first heard the title of Oswaldo Zavala’s Drug Cartels Do Not Exist. The statement seemed a ridiculous provocation: of course drug cartels exist. What other organization could carry out so much violence in the name of illegal profit? But Zavala, associate professor of Latin American literature at the College of Staten Island, draws a critical distinction between drug trafficking and drug cartels. Zavala does not argue that drug trafficking does not exist, nor that the violence associated with the operation is not real. Instead, he examines the language and media through which people discuss and learn about Mexico’s illegal drug industry. Unlike much of the previous academic work and journalism associated with the phenomenon of drug trafficking in Mexico, he keeps a keen eye on the state origins and political functions of drug-trafficking-related violence.

Cartels, Zavala argues, often portrayed as wide criminal networks that dominate the narcotics black market, engaging in all-out war both with each other and the state, are perfectly subject to state control. The plazas (the territory in which the so-called cartels operate, analogous to ‘turf’ in English) are protected by the Mexican military and Federal Police, with corrupt local and federal leaders consciously allowing trafficking to persist–as long as they get their share. The supposed threat that cartels pose to the sovereignty of the state is used as a cudgel by the state to justify and expand its own presence, and expropriate land and resources in the resource-rich territories of northern Mexico.

Even the word ‘cartel’ itself is a contradiction when describing these groups. As Zavala points out in an interview on the podcast TrueAnon, ‘cartel’ is an economic term used to describe a coterie of firms that exercise crushing market power. The label, he says, is technically more appropriate for organizations such as the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, or OPEC. The Mexican government only began using ‘cartel’ to describe drug traffickers after Operation Condor and the Mexican Dirty War of 1968-82. ‘Cartel’ implies collaboration, and yet the Mexican government would also have us believe that incidents of mass violence are a result of wars between these groups of traffickers. The state narrative–what Mexican sociologist Luis Astorga terms the “narco matrix”–distracts us from the material role that the Mexican police and armed forces play in perpetuating violence against Mexican citizens.

The plaza that the so-called cartels operate in and fight over are amorphous; they are retroactively coined, described only when it is convenient for the Mexican state to create a narrative around mass violence. Zavala writes:

I will point out finally that every plaza, that is, every city and region where the state of emergency is visible over the country’s underground economies, is the necessary location of the judicial-police system of sovereignty that…reaffirms itself as the expression of state hegemony over organized crime.

In many cases, the genesis of this discursive matrix is the image of the corpse, which Zavala writes is “constructed as an exercise in semiosis that unnecessarily transforms the victimized body into an empty vessel,” ripe for narrative exploitation. The corpse obscures the political dimension of the so-called War on Drugs in Mexico, and this distortion is particularly egregious in written and televised fiction about the narco, sources which Zavala consistently relies on to advance his argument.

Zavala analyzes journalistic reports, novels, songs, interviews, films, and even his own personal encounters throughout the book. It is fundamentally a media analysis, and an excellent one at that. Its scope assures that even readers unfamiliar with some aspects of narco fiction and narrative will have solid reference points. While readers may not have heard a single song by Los Tigres del Norte, they’ve most likely had some exposure to television shows/films such as Narcos, Sicario, and even The Godfather. And even when analyzing more niche media, Zavala provides a concise summary that assists the reader in understanding his argument. In this way, Zavala’s voice stays relatable, situated within a shared cultural narrative that he proceeds to deconstruct.

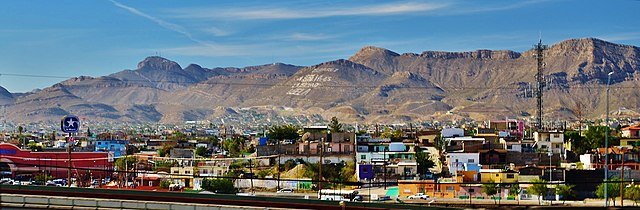

Zavala grew up in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, just across the border from El Paso, Texas, and he frequently brings his narrative back to his hometown. Talking about Sicario’s exaggerated depiction of violence in Juárez on TrueAnon, Zavala, audibly perplexed, stated “What would it have been like to watch that movie in a Juárez movie theater? What would it be like for people watching this like, Oh, we live in the belly of the beast and don’t even realize it.’” In Drug Cartels Do Not Exist, Zavala mentions Juárez more than any other city, and it’s not hard to see why. It is perhaps the most mythologized city in media about the so-called War on Drugs. It has been derided, exalted, sensationalized, reconstructed, imagined, annihilated. Much like the corpse, these literary abstractions can often serve to depoliticize the material reality of the city and the state power to which it is ultimately subject. Zavala has an undeniable stake in this war of words: Juárez is his home.

Throughout the book, Zavala builds his authority through a combination of his rhetorical skills, juarense upbringing, and experience as a journalist working alongside reporters such as Ignacio Alvarado and Julián Cardona. His intuition is first-rate, seemingly guessing at the reader’s next thought. At times, the sheer depth of his knowledge bogs down the narrative, but for a primarily academic work, Drug Cartels Do Not Exist is astoundingly readable.

Despite its readability, Drug Cartels Do Not Exist does have its issues. Divided into four main sections, the individual chapters suffer from what I can only describe as being too self-contained. Each chapter can easily stand on its own, and while this level of thoroughness is effective when discussing a singular aspect of the “narco narrative” such as the reality of state violence or the writers who subvert it, Zavala’s points become repetitive by the end of the book.

Additionally, its academic references can be a bit esoteric to a popular audience; only those with a prior interest in critical academic theory are familiar with Žižek or Fukuyama. However, much like he does with unfamiliar media, Zavala also provides the key points of theorists’ work in order to help the reader understand exactly what he’s trying to get at. For example, Zavala’s definition of the term ‘state’ as “the monopoly to decide” is contingent upon Carl Schmitt’s, which he helpfully introduces by quoting Schmitt directly. As the reader, I felt as if I walked away with more than just Zavala’s thesis, and his footnotes excite me in a way that I’ve never found footnotes to be exciting before.

Why, then, aren’t we taking this thesis seriously in the U.S.? Outside of a few articles in Harper’s and The Nation, the discussion remains relatively obscure. Drug Cartels Do Not Exist was initially controversial after its publication in Mexico in 2018, and this English translation was not published until 2022 by Vanderbilt University Press. Perhaps the reason for its lack of popularity in the States is accessibility, since the book is primarily accessed via online academic databases. Zavala’s new book, La guerra en las palabras. Una historia intelectual del «narco» en México (1975-2020) published in Spanish by Debate (a sub-label of Penguin Random House) in September 2022, seems to be geared towards a more general audience, with a provocative cover that quite literally obscures the reality of drug trafficking in Mexico. I hope that one day it’ll see an English translation, and I hope its publication makes all the right people mad. Only then will we be ready to say confidently: drug cartels do not exist.