Danya Blokh

Solenoid by Mircea Cărtărescu, trans. Sean Cotter, Deep Vellum, 2022, 672 pages, $17.99

“Philosophers thus far have tried to interpret the world,” writes Romanian author Mircea Cărtărescu, parodying Marx. “My goal is to escape it.”

The desire for escape drives the protagonist of Cărtărescu’s surreal novel Solenoid. Though he lives a drab life as a school teacher in late communist Bucharest, the escape he seeks not only represents a more interesting life, but an escape from the very confines of human existence: a transcendence of the three-dimensional limits of our perception, which he describes as a jail cell. The promised portal seems perpetually around the corner, enticing the protagonist with a series of fantastical visions, impossible transmogrifications, and night terrors which blur the boundary between dreams and waking life. Dwarves appear at the foot of his bed and grin up at him inhumanly, then vanish. The stairways of apartment buildings descend into subterranean caves. Abandoned factories house zoological expeditions showcasing enormous, pulsing worms. As if things couldn’t get weirder, the protagonist finds that his house has been constructed upon a solenoid, a coiled wire capable of translating electricity into mechanical work. The solenoid imbues the protagonist’s home with such metaphysical properties as endlessly shifting rooms and a bed where he can levitate while sleeping or making love. Living within the unstable labyrinth would drive most people to seek psychological help. Yet Cărtărescu’s protagonist embraces his newfound situation with sick hope, interpreting the unfathomable as clues pointing him toward the ultimate exit.

Since he began publishing in the late 1970s, Mircea Cărtărescu has achieved international acclaim for his poetry, criticism, and surrealist fiction. Writing for Dissent, critic Matt Weir calls him “perhaps the most acclaimed Romanian writer alive.” In Solenoid, however, Cărtărescu parodies his own literary celebrity. The novel’s protagonist is a thinly veiled alter ego of Cărtărescu himself, one who never achieved success in writing and instead became a school teacher. Despite his modest circumstances, the other Cărtărescu nonetheless threatens to exceed the writer. His alienation from the literary world enables him to write a text deeper than any novel, “a text outside the museum of literature, a real door scrawled onto the air, one that will let me truly escape my own cranium.” To the reader, the protagonist’s life seems like a terrifying fever dream, but Cărtărescu covets the intensity of writing only possible beyond the distractions and commodifications of publishing. He writes:

Only the disdained janitor, grouchy and taciturn, who leaves behind dozens of pages, illustrated with amazing girls, dragons, butterflies, and bloodshed; the lathe worker who keeps a diary meticulously describing his factory shift, how he uses condoms, what he eats and how he defecates; the hairdresser who compulsively details the terrible pains of her fertility treatments…Only they know the best-kept secret of any art: the blind man’s battle and the lame man’s flight—everything else is barren ritual and Pharisaism.

What is this best-kept secret? Its ability to look inward–to train one’s eyes carefully on the barest details of life–so as to find glimmers of transcendence hidden behind the edifice of banality.

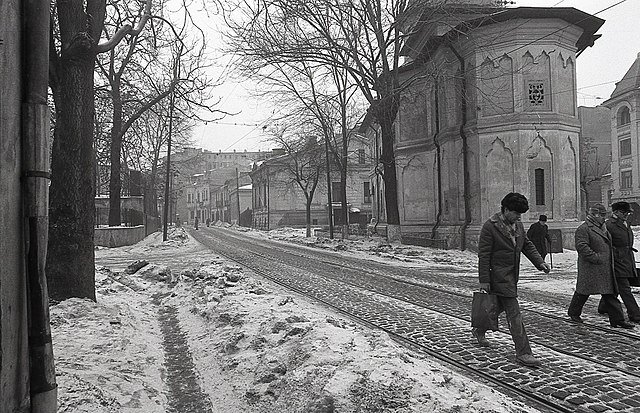

Cărtărescu’s choice to set his novel in Romania, and specifically in the stagnating epoch of late communism, reflects his belief in the value of boredom. Like Cărtărescu himself, Romania has come a long way since the 1980s, becoming a “success story of E.U. expansion” according to New Left Review’s Alexander Clapp. In Solenoid, however, Cărtărescu returns to the era of his upbringing, proposing an inverse relationship between the banality of our surroundings and the extravagance of our imaginations. If deprivation enables us to shift our attention from the material world to the wild fantasies lurking in its interstices, ’80s Bucharest, “the saddest city on the face of the Earth,” provides fantasies in spades. Cărtărescu ruminates beautifully on the city’s gray streets, industrial architecture, and sprawling ruins; this very dilapidation forms a porous barrier between reality and the beyond. When an energy crisis turns out the city’s lights, the stars — Bucharest’s “most beautiful feature” — illuminate the faces of a radical sect of anti-death protesters. By foreclosing distraction, the city’s state of decay forces a confrontation with the barest existential absurdities. The intimate relationship between dereliction and enlightenment becomes clear when Cărtărescu describes Bucharest as “not a city but a state of the spirit, a deep sigh, a pathetic and pointless cry. It is like old people who are nothing more than walking wounds, clots of nostalgia, like dry blood on scraped skin.” Cărtărescu argues that it is precisely such a state of spirit which prepares us to recognize the fissures in the material world, and among them, the possibility of escape.

In this sense, Solenoid, which was written in 2015 and translated into English by Sean Cotter in late 2022, is consonant with the past decade’s resurgent interest in late Eastern European socialism. Lately, many spheres of culture have demonstrated an aesthetic fascination with Soviet post-punk, brutalist architecture, and the morose atmosphere of those dreary, gray times. Though Cărtărescu scathingly satirizes Ceaușescu’s stagnant regime—official “atheism contests,” which involve spitting on Christian icons, are only one example of the book’s ideological absurdities—his choice to set Solenoid in that particular gloomy era illuminates the source of late socialism’s aesthetic appeal in contemporary culture. In a proudly materialistic world, full of shiny but hollow distractions, there is a certain nostalgia for an era when that hollowness was made explicit, when the dreariness of the exterior world corresponded to the gloom one felt, and when spiritual survival was possible only through turning inward. Cărtărescu is no communist by any stretch of the imagination, but in demonstrating the radical creativity made possible by communism’s barren landscapes, he casts a skeptical shadow on capitalism’s all-encompassing grasp.

Solenoid’s skepticism calls to mind another work of post-socialist Eastern European fiction, the novel Homo Zapiens by Russian author Victor Pelevin. Like Cărtărescu’s narrator, the protagonist Bablyn Tatarsky is a former author rejected by the literary world. Also like Cărtărescu’s narrator, Tatarsky experiences a series of supernatural encounters which he interprets as a trail of clues, and these signs ultimately lead him to uncover a conspiratorial order underlying post-Soviet Russia. Yet Homo Zapiens is pure postmodernism, blending the commercial with the serious to create a world devoid of meaning, truth, or reverence: a world in which the ghost of Che Guevara suddenly appears to deliver a lecture on advertising strategy. This is a world molded by the invisible hands of the marketplace, so all-penetrating that when Tatarsky uncovers the scheme at the end of Homo Zapiens, he also learns that it has long ensnared him. By contrast, Solenoid’s late communist Romania keeps the dream of escape alive, tucked away in the smallest and most obscure places. The protagonist’s sincere belief in enlightenment provides the book’s melancholy core. Cărtărescu does not denigrate the sacred so much as elevate the unholy, betraying a powerful and almost classicist belief in truth—evasive, yes, but intelligible in the strange visions, dreams, mathematical theories, and historical oddities the protagonist investigates in his search of a dimension beyond our own. Fittingly, when Cărtărescu’s protagonist uncovers Solenoid’s underlying conspiracy—a brood of supernatural creatures are feeding off the pain of Bucharest’s residents to power their extraterrestrial escape—he, unlike Tatarsky, evades their scheme and succeeds in his long-desired escape. This ending is Solenoid’s only weakness: running away from aliens feels far too simple a conclusion to the novel’s all-pervasive search for existential relief. Yet it reveals an optimism still available in 1980’s Eastern Europe that would become foreclosed in the ’90s—an alternative space for imagination, an escape that was more than mere escapism.

It is Cărtărescu’s sincerity, more than his nightmarish imagination or eloquent writing, which makes Solenoid such an uncommon and refreshing book. For all its depressive musings about existence, its equation of humans with “hams [packed] into our soft sacks of gristle and bones,” its definition of living as enduring the knowledge that we are “going to suffer and then disappear and never give the world any meaning,” Solenoid preserves a hopeful vestige for the possibility of something numinous hidden in the material realm. Moreover, for a book that so ruthlessly parodies the literary world, Solenoid conveys a potent faith in literature to elucidate the path toward transcendence. Much as Plato’s undeniably poetic Republic legitimates itself by claiming to reject poetry, Cărtărescu’s repudiation of literature brings him back to its forgotten promise: the ability to examine mundanity, to find meaning in reality’s slips and turns, to see the limits of our existence and imagine a way beyond.